Human Rights and Immigration Lawyer Contact Me

Remembering Fred Korematsu

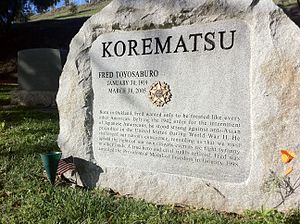

English: Gravestone of Fred Korematsu at Mountain View Cemetery, Oakland, CA (Photo credit: Wikipedia)

Fred Korematsu would have turned 94 today. This post is in honor of his legacy of rabble-rousing. He challenged his internment, only to have the Supreme Court justify Japanese internment for “national security” reasons. It is pretty well established that Korematsu v. United States was wrongly decided. However, it is important to revisit and re-remember Korematsu because it exposes the racism and poverty of liberal thought in American legal jurisprudence, by exposing the legal fiction of levels of scrutiny

In Korematsu, the Court upheld the conviction of Mr. Korematsu, a Japanese-American, who had failed to evacuate his home as ordered by the military. The Court stated that “all legal restrictions which curtail the civil rights of a single racial group are immediately suspect” but did not apply the rule. If the Court had applied strict scrutiny, Korematsu would be ripe with over-inclusivity and under-inclusivity problems, such that the detention of Japanese would not show narrow-tailoring to fulfill a compelling government interest. Korematsu was over-inclusive because loyal Japanese were swept up but it was also under-inclusive because Germans and Italians were only marginally detained.

An originalist critique of Korematsu also exposes the decision as wrong. While the Court upheld Mr. Korematsu’s conviction based on military necessity, nothing in war powers given to Congress and Executive means they can take any action deemed expedient or suspend habeas corpus. In fact, Framers distrusted unlimited powers and martial law, which is why they gave each branch of government limited and enumerated powers, not to be suspended. Yet, the legacy of this wrongly decided decision pervades our existence, and exposes the underlying racism of American jurisprudence

Korematsu exposes the inherent racism of the legal system. Korematsu is the case that held “all legal restrictions which curtail the civil rights of a single racial group are immediately suspect” and yet, on that day, Mr. Korematsu was only the suspect. In Grutter v. Bollinger, one of the Michigan affirmative action cases, the Court states that the lesson from Korematsu is that national security constitutes a “pressing public necessity” such that the government can use race. Thus, Korematsu legitimizes invidious group-based discrimination in the name of national security. It completely violates the spirit of due process, as not a single Japanese was found to be a spy during World War II.

This makes Korematsu contrary to the liberal principle of individual rights. Much like Derrick Bell’s The Space Traders where blacks were asked to perform a civic duty, in Korematsu, the Japanese were asked to carry out a civic duty by subjecting themselves to detention. But there is no such civic duty when it comes to whites. This civic duty is reserved for racial and ethnic minorities. Indeed, in post 9-11 America, programs such as NSEERS targeted Arab Americans and South Asians based on the same rationale – that minorities have a civic duty to sacrifice themselves for the greater good due to the actions of a few people who belonged to that group.

Whites have no similar duties – they are simply individuals who are afforded the protection of the Fourteenth Amendment because they suffer from reverse discrimination. But racial and ethnic groups who are constantly racially profiled, discriminated against and subject to suspect classification, are not afforded these protections because they can’t prove disparate treatment when the racial legal order endorses group-based disparate treatment.

Most importantly, Korematsu does not stand for the proposition that all use of race is suspect but rather, only discriminatory use of race is constitutionally suspect. In Adarand v. Pena, the Supreme Court majority relied on Korematsu to use strict scrutiny to strike down a government program that used benign race classifications. But Korematsu does not stand for the proposition that remedial programs should be subject to strict scrutiny. Instead, as the dissent in Adarand notes in a footnote, Korematsu specifies that “all legal restrictions which curtail the civil rights of a single racial group are immediately suspect.” The programs at issue in Adarand, and the affirmative action cases such as Bakke, Grutter and Fisher, do not “curtail the civil rights of a single racial group.” They involve the benign use of race distinctions to advance a legitimate government interest in tackling the vestiges of past and present discrimination. A strict reading of Korematsu would hence give strict scrutiny a different meaning—strict scrutiny should be limited to “all legal restrictions that curtail the civil rights of a single racial group.”

This does two things. First, such a re-definition of strict scrutiny looks like the intermediate scrutiny in the Metro Broadcasting, where the Court drew a bright-line between the use of race for invidious discrimination and the benign use of race. And second, it exposes the tiers of scrutiny as legal fiction, constructed by a Court that is unable to deal with race and race relations, and applied inconsistently. If all use of race is actually not suspect and Korematsu’s strict scrutiny is really the intermediate scrutiny of Metro Broadcasting, then affirmative action and other remedial programs would be legal without more. But a re-reading of Korematsu exposes the tiers of scrutiny as legal fiction, and maybe something the Court should reconsider.

Perhaps then, Korematsu’s biggest legal significance is in realizing that it does not deviate from the norm. It is normative because it exposes racism and the legal fiction of tiers of scrutiny. Korematsu was the logical extension of the history of American race relations with Asian Americans. From People v. Hall, where a Chinese were not allowed to testify on the basis of their race, to the Chinese Exclusion Act, to Gong Lum v. Rice, where an Asian girl could not attend a whites-only school to the Court’s decisions to restrict citizenship to white people (Ozawa, Thind), Korematsu is a legal manifestation that Asian Americans are the inassimilable Other who can never become a part of the political community so exclusively defined by the Court in Dred Scott. Today, such race-based exclusion remains the law of the land.

And so we remember Fred Korematsu, who told us to struggle, even in the face of state-sponsored exclusion.

Related articles